Humans can balance almost anything. From bikes to rails to handstands on other people, our bodies have the amazing ability of automatically correcting balance. Balancing tasks are fun and engaging activities because they are dynamic, require full attention, and test reactions. But they can also be mysterious and frustrating to learn. How can we learn to pull off these incredible feats of balance?

This is the beginning of a four-part series on how to balance anything:

The Biomechanics of Balance

Balancing Yourself

Balancing Objects

Balancing (on) Other People

The goal of this series is to provide a blueprint for learning any balancing task. We will connect theory and practice through exploring the dynamics of various balancing activities and turning the concepts into targeted exercises. This will provide the foundations to analyze balancing tasks, develop training strategies, and troubleshoot issues.

In this first post, we will outline the biomechanics of balance, covering the basic physics of balance and how balance is controlled.

Basics of Balance

To understand balance, we need to know about center of mass and base of support.

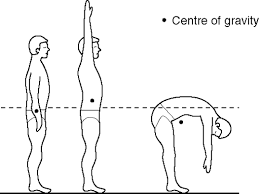

Center of mass (CoM) is the position that represents the average mass of an object. Note that this point can be outside of the object.

Base of support (BoS) is the area beneath an object where it makes contact with the ground. This includes the space between each point of contact.

Balance is as simple as keeping the CoM over the BoS. That’s all that’s happening in the motorcycle image, the CoM is over the BoS, and as long as there aren’t external forces — like someone pushing it, or a gust of wind — it will stay balanced.

While being able to balance a motorcycle on its kickstand is impressive, there isn’t any balancing; it’s placed into a state of balance. When we balance something, it’s dynamic, we are constantly trying to correct a state of imbalance. We continually need to identify the direction and amount we are out of balance, then make a corrective action. This process is what makes balancing tasks fun.

Controlling Balance

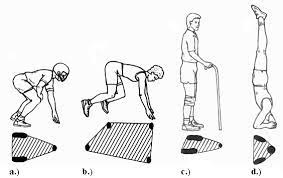

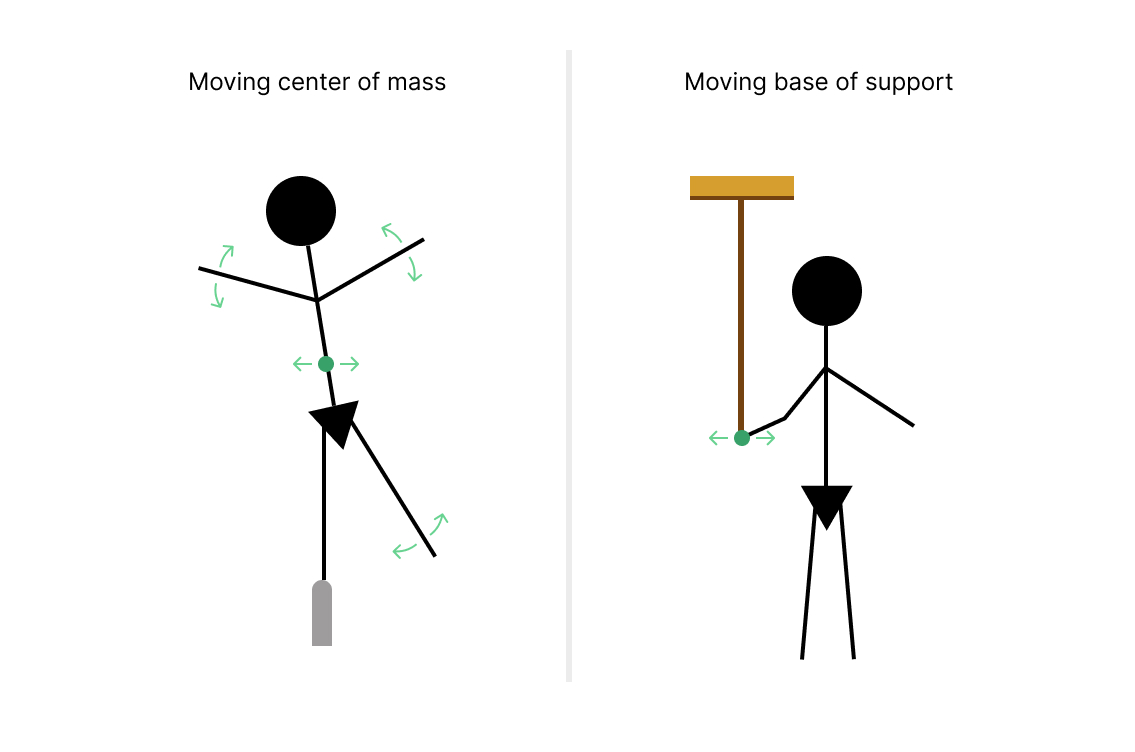

Since an unbalanced state is when the CoM isn’t over the BoS, there are two ways we can correct this.

Moving the CoM

Moving the BoS

The type of correction depends on what is being balanced. If you’re balancing yourself, generally you’ll be moving the CoM (eg. balancing on a rail). By moving your arms and legs, you change the position of your CoM to stay above your BoS (the rail). If you’re balancing an object, you’ll be moving the BoS (eg. balancing a broomstick on your hand). By moving your hand, you can keep the BoS underneath the CoM of the broomstick. Some balancing tasks will involve both, such as balancing other people or balancing yourself on a moving BoS (eg. slackline).

So how do we get better at controlling balance? To answer this we need two more concepts: zone of stability and central behavior.

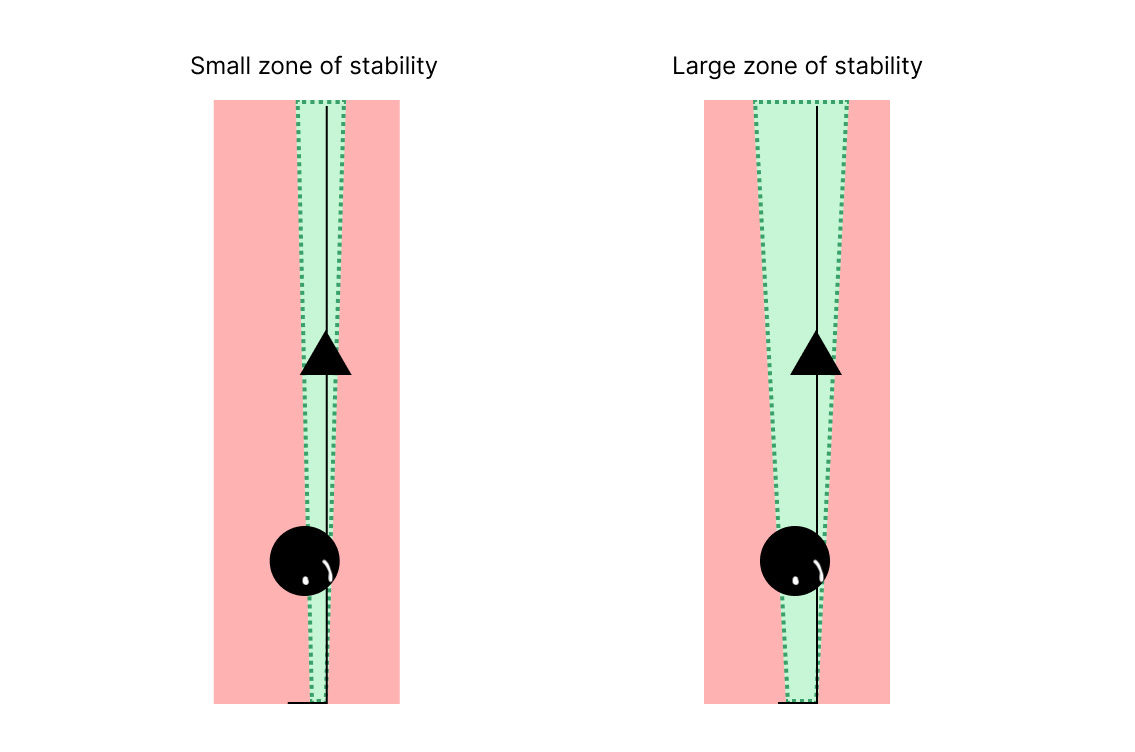

Zone of stability (ZoS) is the range of positions that an object can be in without falling over. Basically, how far off center the CoM can be while maintaining balance. The following image shows small and large ZoS for a handstand. Outside of the green area, the handstand will fall.

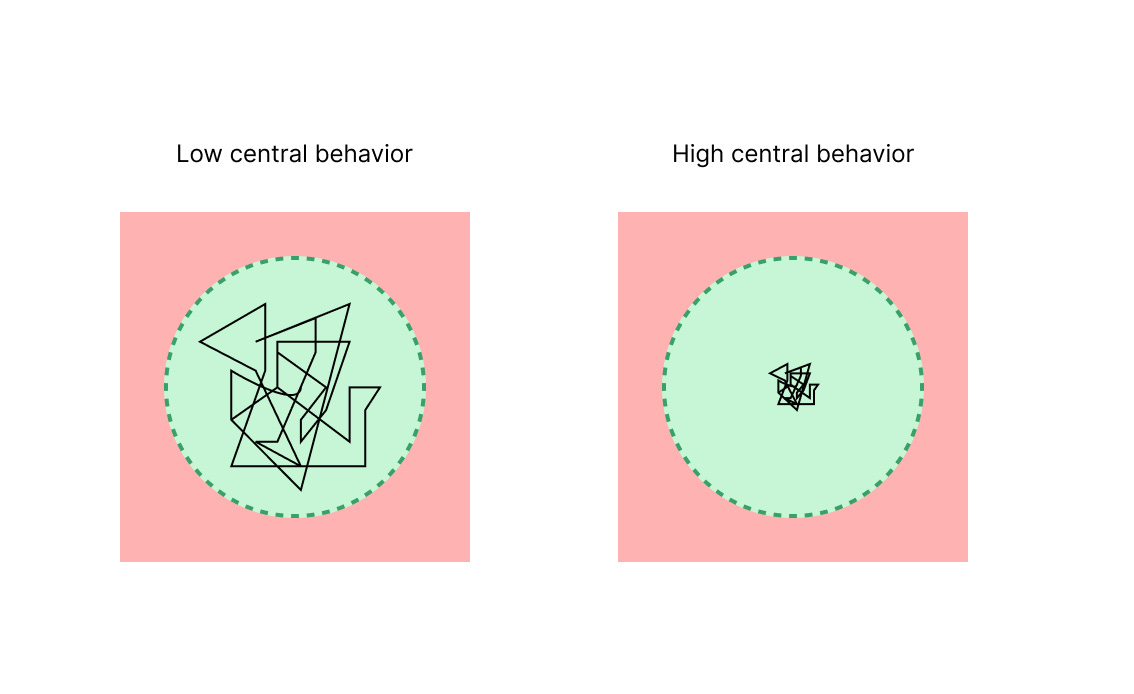

Central behavior (CB) is the tendency of an object to spend more time near the center of its base of support. This is done by performing rapid micro-corrections that minimize postural sway, making the object look still (like the balancing motorcycle). The following image shows paths of the CoM over time within the ZoS, illustrating low and high CB.

ZoS precedes CB — if you can’t make corrections, you can’t stay centered. Thus, ZoS drills should be a larger portion of a beginner’s training. Working on the ZoS helps explore the dynamics of the balancing task and develop coordination. Where is center? What does falling feel like? How much is it falling and in which direction? What movement is necessary to correct this fall? How much force is required? As the body learns these, it gets better at making larger saves, increasing the ZoS.

But staying balanced is just the first step, the ultimate goal is to achieve a steady balance, which happens by improving CB. CB makes a balance task look controlled. The body is constantly identifying and correcting imbalance, but it happens so rapidly that it looks still. This acute perception and coordination creates the precision required to achieve higher level skills. High CB is the best indicator of proficiency and CB training will become a significant focus for advanced balancers.

Future parts of this series will use ZoS and CB as core concepts for learning to control balance.

From Concepts to Practice

These concepts give us the foundational dynamics of balancing tasks. Now that we know what makes something unbalanced and what can be done to correct it, we can deconstruct tasks and identify weak points. This analysis informs the creation of targeted exercises. Additionally, these concepts provide clearly defined subgoals for balance training — improve ZoS and CB. All of this is critical for developing effective training strategies and troubleshooting issues.

In the next parts of this series, we will apply these concepts to three different categories: balancing yourself, balancing objects, and balancing other people. Each category has its own challenges and strategies, but they all share the same underlying principle — keep the CoM over the BoS.